Osage County

Osage County is the largest in Oklahoma, and until recently it was Oklahoma’s only reservation. The land has a unique history within Indian Country as a result of the process of allotment begun over a century ago.

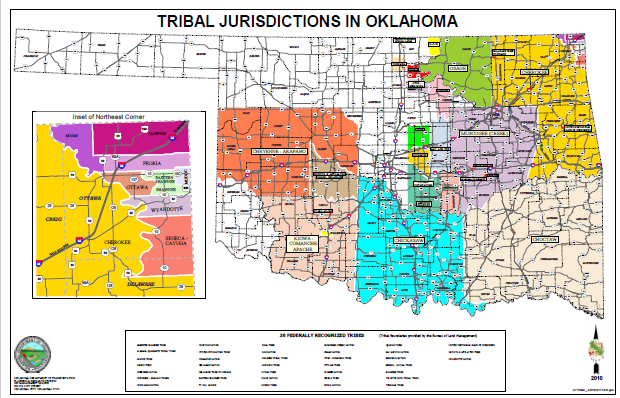

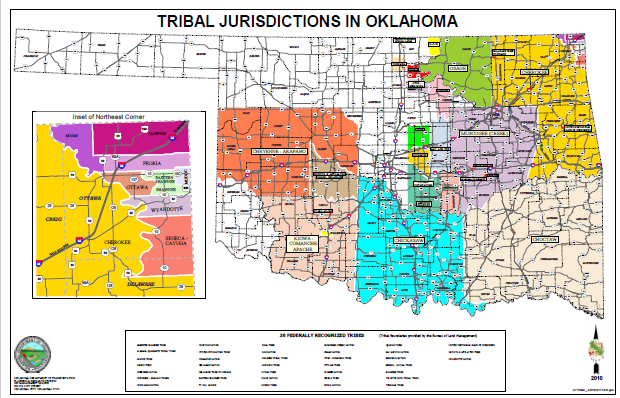

View map.

Osage County is approximately 1,470,059 acres

By the mid 19th century the Osage had a reservation in southern Kansas, but following the Civil War the state saw a huge influx of settlers, and that included an influx of intruders onto the reservation. Growing tensions between the Osage, settlers, and the state of Kansas brought about several attempts to buy Osage lands. Although the Osage opposed and resisted these attempts, by spreading rumors of massacre the Commissioner of Indian Affairs was able to coerce a number of Osage representatives into signing the Drum Creek Treaty in 1868

This treaty would however, be contested, with all sides opposing different terms of the treaty. Instead, in 1870 Congress passed the Osage Removal Act that enabled the Osages to sell their lands in Kansas and buy a new reservation in Indian Territory to the south, where the Cherokee, Seminole, Creek, Choctaw, and Chickasaw had been punitively forced to sell sections of their territories for their role in the Civil War. As terms of the legislation Congress appropriated a $50,000 loan for the expenses of removal and fixed the sale-value of the Osage lands in Kansas at $1.25 per acre. These lands accounted for some 8,000,000 acres, although the final sale-price did not compensate Osages for any property they had on those lands, and expenses of the Removal were deducted from that price - including those fees accrued from Kansas state mismanagement

The Osage eventually selected lands just south of the Kansas border in the Cherokee Outlet, which they were able to buy for $0.70 per acre, although both the Osage and the Cherokee were unsatisfied with this price. The Osage purchased a significantly smaller reservation of 1,470,059 acres at the price of $1,029,041.30, which Congress approved in 1872. The Osage and the Kaw are the only tribal nations in Oklahoma to buy their reservations. By purchasing their lands, these nations secured the right to hold them in common while also possessing fee simple title to those lands, which consequently protected them from both the Dawes and Curtis Acts

At the turn of the 20th century, the Osage continued to assert rights to their tribal territory and had resisted attempts to disestablish the reservation. Osage land ownership however, obstructed the process of statehood for Oklahoma, and in 1906 the Osage signed the Osage Allotment Act. The Osage were under pressure to allot their lands, but were able to use their ownership of the land as political leverage. The Osage Allotment Act was drafted by the tribe, and unlike the majority of reservation allotments, the tribe relinquished only those lands they considered undesirable. The entire rest of the reservation was divided amongst tribal members in parcels of some 675 acres, while the tribe maintained communal mineral rights, which to this day are held in trust by the federal government

Reservation lands were allotted in three separate rounds. In the first of these, tribal members selected lands that would be their ‘homestead’, which could not be taxed or sold. Those lands chosen in the second and third rounds could be taxed after three years and sold after 25. 4 types of reservation lands were exempt from this allotment: 1) camp reserves (also known as Indian Villages) and agency reserves 2) railroad right of ways 3) gifts to individual tribal members 4) townsites including Fairfax, Foraker, Hominy, Pawhuska, and Barnsdall

In the years after statehood, Oklahoma did not recognize Osage County as a reservation, though the federal government did because the tribe maintained a mineral reservation. In 2010, the exact status of the reservation was challenged in Osage v. Irby. The contention within Irby was over the right of Oklahoma to tax the income of tribal citizens employed and living in the Osage reservation. The right to tax then hinged on whether or not Osage county was legally a reservation.

The Court recognized that the 1906 allotment legislation does not explicitly disestablish the reservation and is in that respect ambiguous. Existing precedent for termination and the disestablishment of reservations requires there to be explicit evidence or language to that effect. Against this tradition however, the Tenth Circuit Court turned to circumstantial evidence

The Court cited as evidence the influx of non-Osage residents into the county after Oklahoma gained statehood, and historical accounts that claimed the reservation had been disestablished, despite the continuity of Osage communities and federal legislation that explicitly names the territory a reservation. The Court also noted that the Osage were keenly aware of contemporaneous allotment processes in Indian Territory in which tribal reservations had been disestablished. The Court determined that this knowledge implies Osages must have also known allotment was intended to eliminate their own reservation, ignoring the unique agency the tribe had in crafting its allotment legislation. The Court also cites Oklahoma’s assertion of jurisdictional authority over Osage County as evidence that the reservation had been dissolved, although state jurisdiction does not universally indicate disestablishment. Similarly to Sherrill v. Oneida, the Court also claims that the Osage had only recently attempted to reassert claims to reservation status and tribal jurisdiction, ignoring the long history of Indian policy that has prohibited tribal nations from asserting land claims

The Court ultimately determined that the 1906 Allotment Act had disestablished the reservation, and therefore the state of Oklahoma had the right to tax all individuals in Osage County

View map.

Osage County is approximately 1,470,059 acres

(Osage, 2010, 15)

and can be seen in north-central Oklahoma along the Kansas border. The land was allotted in the early 20th century, with 0.04% of the surface territory still held in trust today. At the same time however, the tribe maintains collective ownership of the mineral estate below these lands, which the federal government holds in trust for the tribe. The state of Oklahoma has asserted degrees of jurisdiction over the territory in the past century, but because of the mixture of surface allotment with collective mineral rights, it wasn’t until 2010 that federal courts ruled that the Osage reservation had been disestablished more than a hundred years earlier in the 1906 Osage Allotment Act (Osage, 2010)

.By the mid 19th century the Osage had a reservation in southern Kansas, but following the Civil War the state saw a huge influx of settlers, and that included an influx of intruders onto the reservation. Growing tensions between the Osage, settlers, and the state of Kansas brought about several attempts to buy Osage lands. Although the Osage opposed and resisted these attempts, by spreading rumors of massacre the Commissioner of Indian Affairs was able to coerce a number of Osage representatives into signing the Drum Creek Treaty in 1868

(Burns, 2004)

.This treaty would however, be contested, with all sides opposing different terms of the treaty. Instead, in 1870 Congress passed the Osage Removal Act that enabled the Osages to sell their lands in Kansas and buy a new reservation in Indian Territory to the south, where the Cherokee, Seminole, Creek, Choctaw, and Chickasaw had been punitively forced to sell sections of their territories for their role in the Civil War. As terms of the legislation Congress appropriated a $50,000 loan for the expenses of removal and fixed the sale-value of the Osage lands in Kansas at $1.25 per acre. These lands accounted for some 8,000,000 acres, although the final sale-price did not compensate Osages for any property they had on those lands, and expenses of the Removal were deducted from that price - including those fees accrued from Kansas state mismanagement

(Burns, 2004)

.The Osage eventually selected lands just south of the Kansas border in the Cherokee Outlet, which they were able to buy for $0.70 per acre, although both the Osage and the Cherokee were unsatisfied with this price. The Osage purchased a significantly smaller reservation of 1,470,059 acres at the price of $1,029,041.30, which Congress approved in 1872. The Osage and the Kaw are the only tribal nations in Oklahoma to buy their reservations. By purchasing their lands, these nations secured the right to hold them in common while also possessing fee simple title to those lands, which consequently protected them from both the Dawes and Curtis Acts

(Burns, 2004)

.At the turn of the 20th century, the Osage continued to assert rights to their tribal territory and had resisted attempts to disestablish the reservation. Osage land ownership however, obstructed the process of statehood for Oklahoma, and in 1906 the Osage signed the Osage Allotment Act. The Osage were under pressure to allot their lands, but were able to use their ownership of the land as political leverage. The Osage Allotment Act was drafted by the tribe, and unlike the majority of reservation allotments, the tribe relinquished only those lands they considered undesirable. The entire rest of the reservation was divided amongst tribal members in parcels of some 675 acres, while the tribe maintained communal mineral rights, which to this day are held in trust by the federal government

(Burns, 2004)

.Reservation lands were allotted in three separate rounds. In the first of these, tribal members selected lands that would be their ‘homestead’, which could not be taxed or sold. Those lands chosen in the second and third rounds could be taxed after three years and sold after 25. 4 types of reservation lands were exempt from this allotment: 1) camp reserves (also known as Indian Villages) and agency reserves 2) railroad right of ways 3) gifts to individual tribal members 4) townsites including Fairfax, Foraker, Hominy, Pawhuska, and Barnsdall

(Burns, 2004)

.In the years after statehood, Oklahoma did not recognize Osage County as a reservation, though the federal government did because the tribe maintained a mineral reservation. In 2010, the exact status of the reservation was challenged in Osage v. Irby. The contention within Irby was over the right of Oklahoma to tax the income of tribal citizens employed and living in the Osage reservation. The right to tax then hinged on whether or not Osage county was legally a reservation.

The Court recognized that the 1906 allotment legislation does not explicitly disestablish the reservation and is in that respect ambiguous. Existing precedent for termination and the disestablishment of reservations requires there to be explicit evidence or language to that effect. Against this tradition however, the Tenth Circuit Court turned to circumstantial evidence

(Osage, 2010)

.The Court cited as evidence the influx of non-Osage residents into the county after Oklahoma gained statehood, and historical accounts that claimed the reservation had been disestablished, despite the continuity of Osage communities and federal legislation that explicitly names the territory a reservation. The Court also noted that the Osage were keenly aware of contemporaneous allotment processes in Indian Territory in which tribal reservations had been disestablished. The Court determined that this knowledge implies Osages must have also known allotment was intended to eliminate their own reservation, ignoring the unique agency the tribe had in crafting its allotment legislation. The Court also cites Oklahoma’s assertion of jurisdictional authority over Osage County as evidence that the reservation had been dissolved, although state jurisdiction does not universally indicate disestablishment. Similarly to Sherrill v. Oneida, the Court also claims that the Osage had only recently attempted to reassert claims to reservation status and tribal jurisdiction, ignoring the long history of Indian policy that has prohibited tribal nations from asserting land claims

(Osage, 2010)

.The Court ultimately determined that the 1906 Allotment Act had disestablished the reservation, and therefore the state of Oklahoma had the right to tax all individuals in Osage County

(Osage, 2010)

.