Cobell Settlement

The Cobell settlement was the result of a fifteen year class action suit against the Department of the Interior for decades of mismanagement of Individual Indian Money (IIM) accounts held in trust by the federal government. The case began in 1996 and the settlement of $3.4 billion was finalized in 2009. The mismanagement of these funds was not a new revelation at the beginning of the suit, but had been under investigation by various groups, including a Congressional committee, for several years. The settlement stipulates that $1.4 billion will go to the plaintiffs of the suit, and the remaining $2 billion is designated to tribes that were impacted by the Dawes Act of 1887.

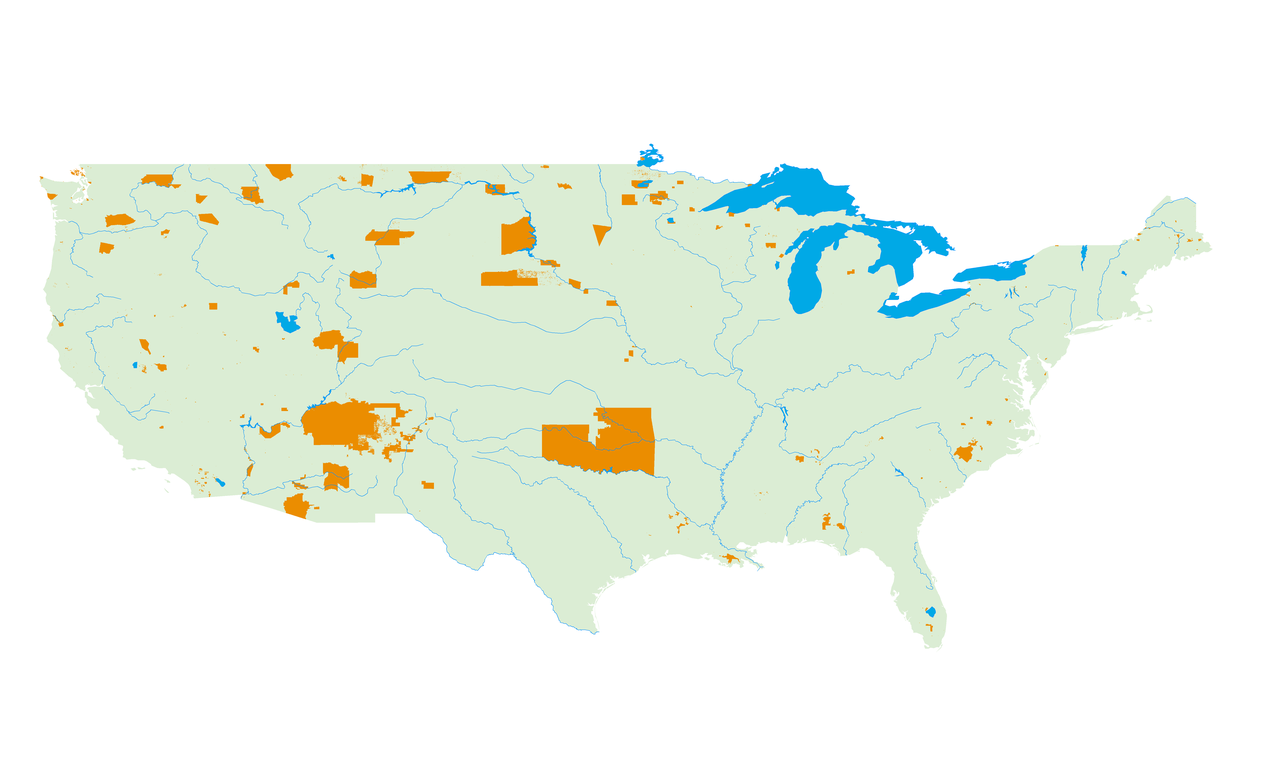

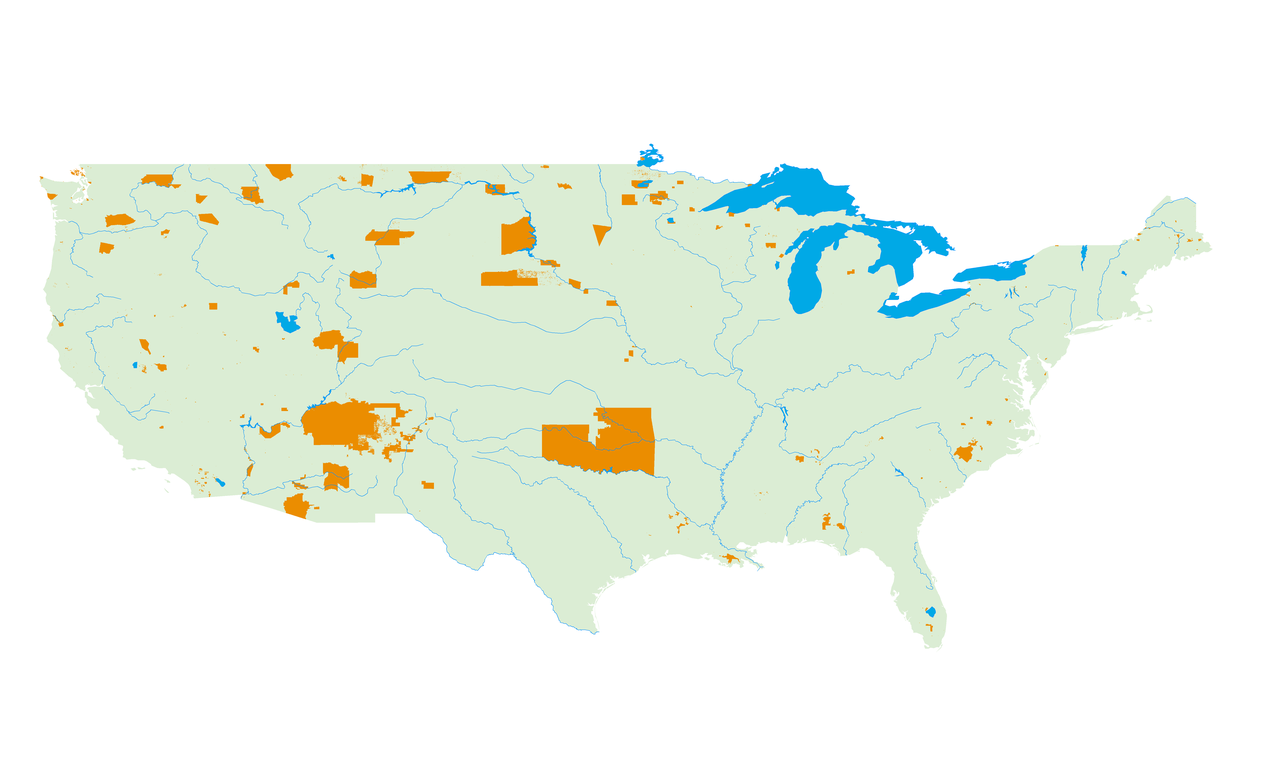

The reason why only Native areas within the contiguous United States are represented in the Cobell settlement is in part because Alaskan Native and Hawai’ian Natives operate under different relationships to the federal government, and were not impacted by the Dawes Act. The process of allotment was implemented and ended prior to indigenous and settler relationship between Alaskan Natives and Hawai’ian Natives were formalized, and land use was negotiated. No reservations or other Native lands in Alaska or Hawai’i were considered eligible under the Cobell Settlement.

View full-sized image

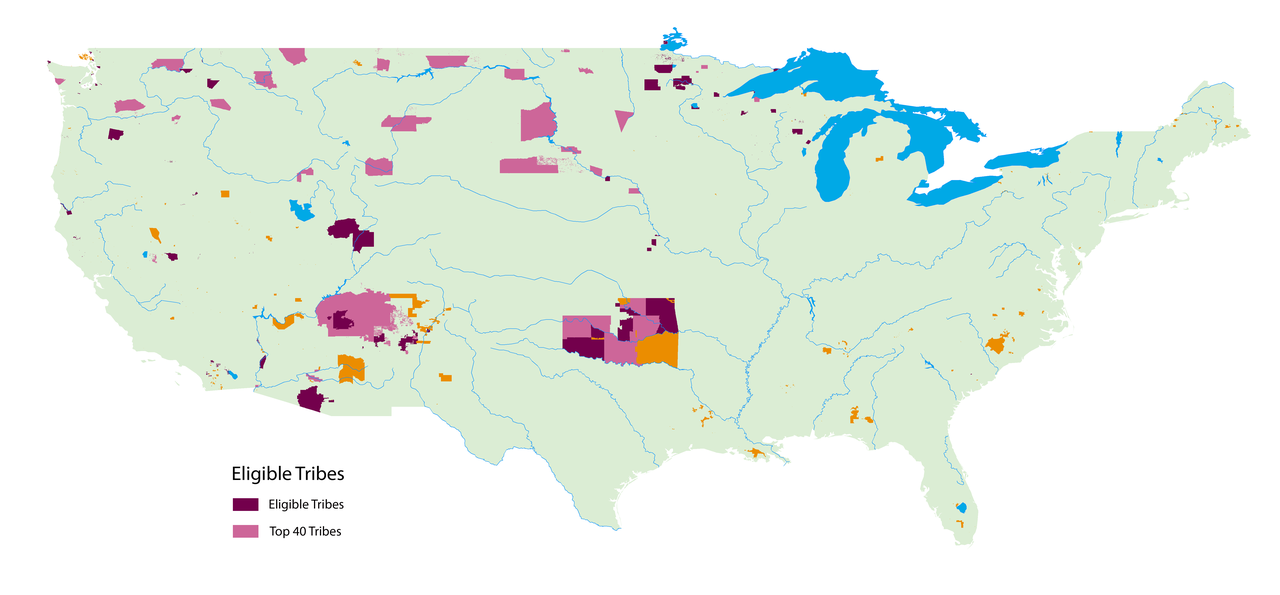

The map above shows all of the Native areas within the contiguous United States as defined by the 2010 United States Census. There are several areas that are designated Native areas which are not in fact reservations, but are lands that are held in trust by the federal government. This is particularly prevalent amongst the tribes that are now in Oklahoma. For example, Osage County, which is no longer considered a reservation by the federal or state governments is still represented as Native land.

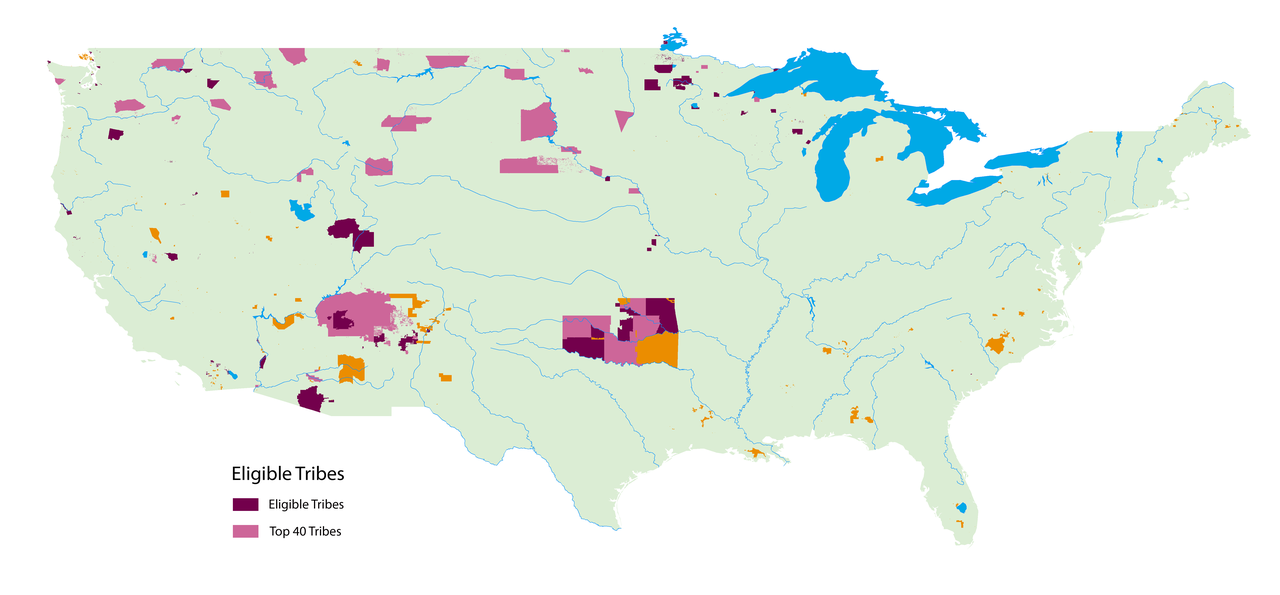

One of the ways that the Department of the Interior has chosen to categorize the tribes eligible to participate in the Land Buy-Back program aspect of the Cobell Settlement is by determining which tribes have the highest rates of fractionation and prioritizing funds from the settlement to those tribes for land buy-back.

View full-sized image

The Department of the Interior designated forty tribes to be allocated $1.39 billion out of the $1.55 billion for fractionated land buy-back settlement funds, which leaves $163 million for the other 110 tribal lands with fractionated interests. These tribes in the "Top 40" are considered to be tribes most impacted by fractionation. Many of these tribes are concentrated in the middle of the contiguous United States, such as the Rosebud Sioux reservation and the Lake Traverse Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate reservation.

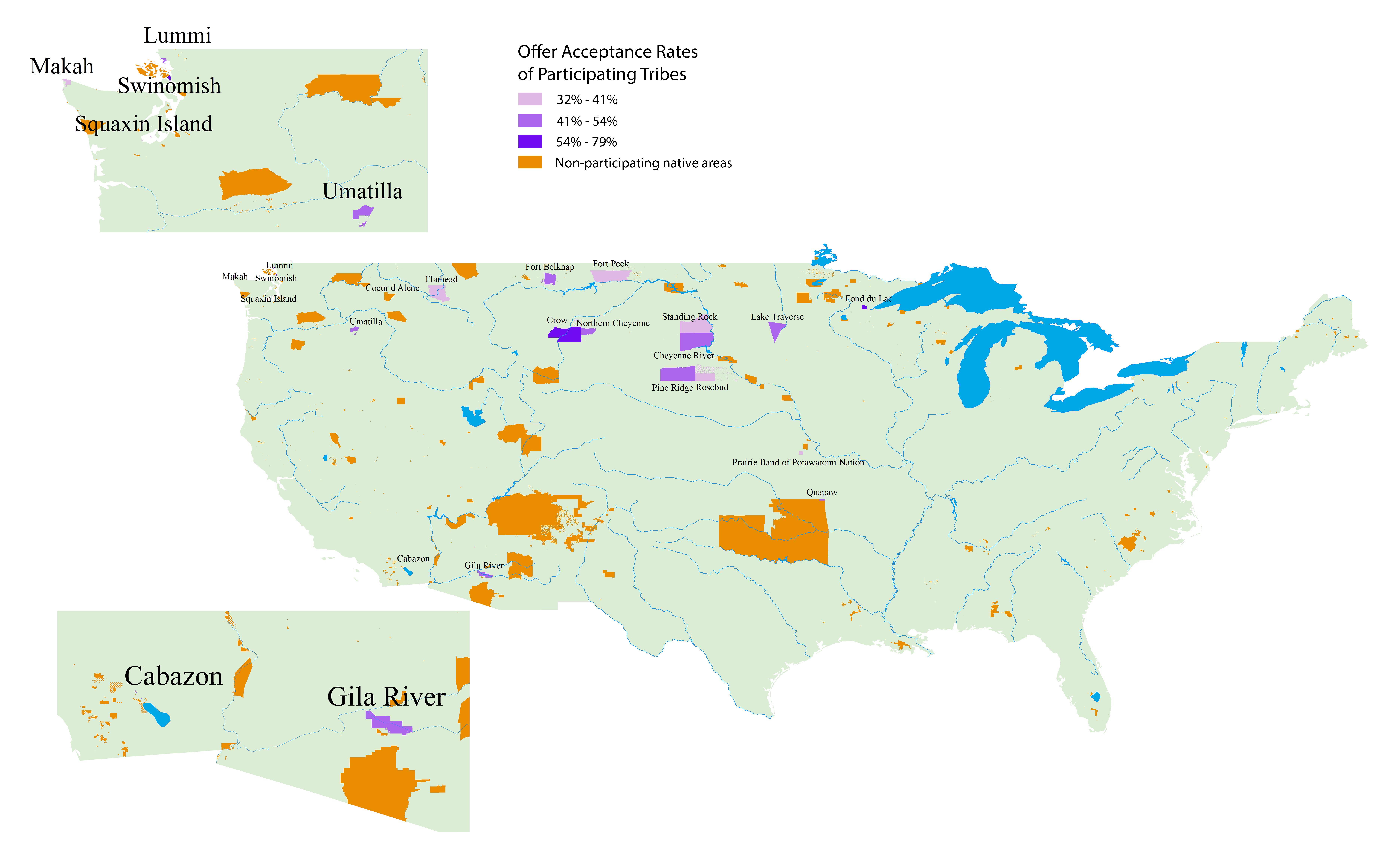

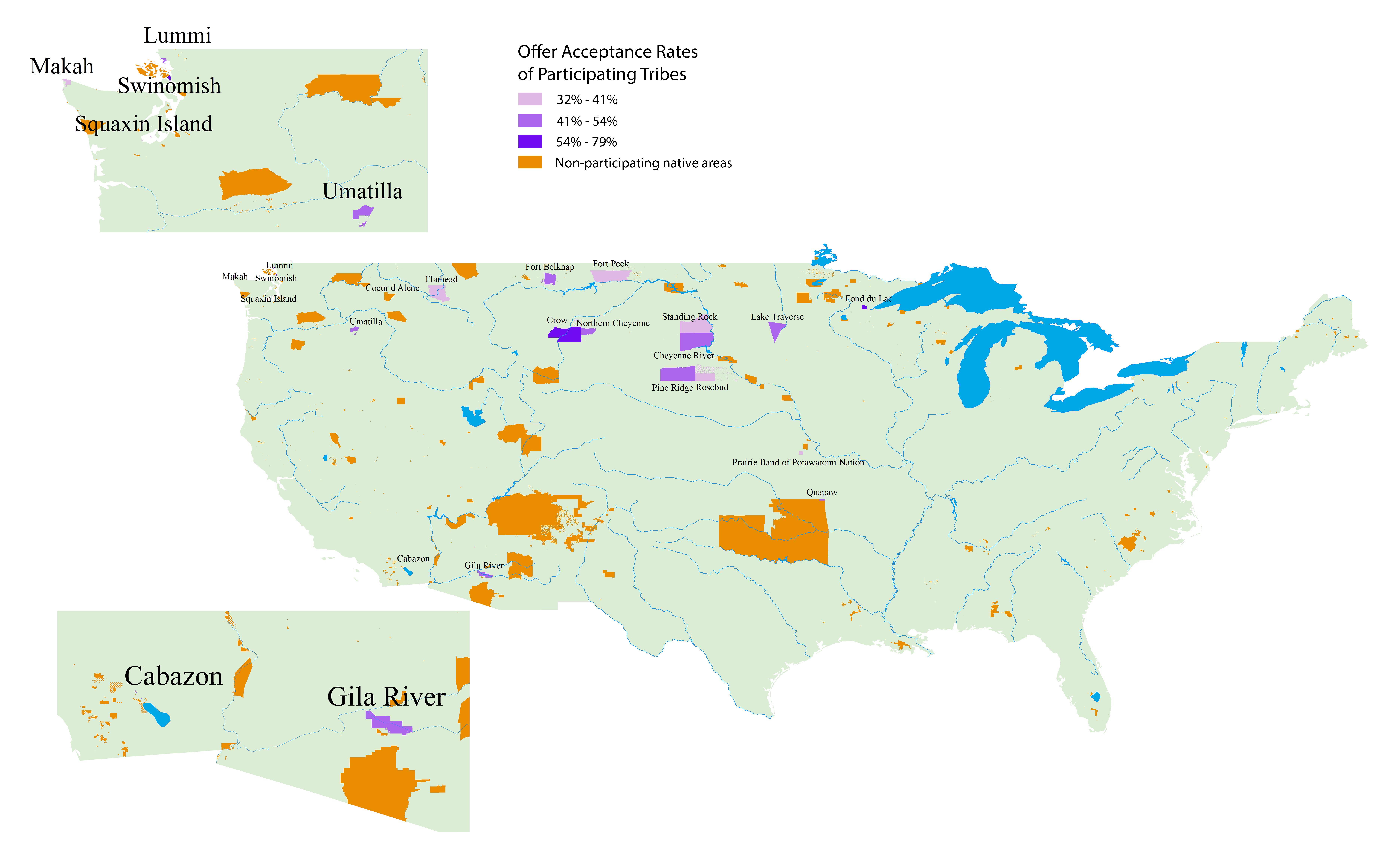

Since 2014 eighteen tribes have participated in the DOI's land buy-back program. The way that these program is implemented in a particular area is as follows. The DOI and the BIA hold many informational sessions in concert with tribal governments to inform people with IIM accounts about the process. The DOI determines the value of all fractionated land holdings in that land area, lands with valuable natural resources like minerals or oil will are considered more valuable than land that is used for agriculture or residences. Each IIM landholder is sent a monetary offer for their land which they can accept or refuse. If an IIM landholder accepts the offer made by the DOI their land will be purchased and put into trust for the tribe in question under the federal government.

View full-sized image

Unsurprisingly, many of the tribes that have participated most in the buy-back program are those tribes within the “Top 40” determined by the DOI. Though the ranges of accepted offers by people with IIMs is large, it is significant that acceptance rates begin at about 33%, or at least one third of offers made by the DOI by were accepted participating tribal members.

Reactions concerning the Cobell Settlement amongst Natives is not monolithic. People unsure about the benefits of tribes engaging in the settlement cite the initial mismanagement by the BIA and DOI as a good reason to decline any further offers concerning land from the federal government. Another concern is how much money is focused in on only forty tribes amongst hundreds that could possibly want to participate in a land buy-back program. This is complicated due to the legal process that confines the settlement in terms of historic legislation such as the Dawes Act, rather than general principles of land relations between the federal government and Native people. Additionally there is frustration with the valuation of the lands under review for buy-back, from the beginning of the Cobell suit there was great discrepancy in the amount of liability concerning mismanaged IIM accounts, ranging from $176 billion to numbers in the low millions of dollars.

Natives who are in favor of engaging with the settlement are often focused on bringing more land into the collectivity of a tribe, rather than held solely by individuals, especially the small plots caused by fractionation. The victory of the Cobell suit is certainly a historic moment in the legal relations between Native people in the United States and the federal government, as it is often considered the largest successful class-action lawsuit in the history of the United States. And the success of the suit can be understood as a loud recognition of the mistreatment and continued mismanagement of Native people’s land by the federal government.

The nature of the Cobell settlement and the subsequent land buy-back program implemented by the Department of the Interior and the Bureau of Indian Affairs is tied up in legacy of the settler colonial state that is the United States. The logic of a settler state is to limit, if not destroy the indigenous peoples and their practices, including their land use practices and sovereignty. The question that the question that Cobell settlement asks is whether engagement with the federal government of the United States on a legal basis is a worthwhile path towards Native sovereignty or if it simply reinforces the authority and power of the federal government over Native peoples and Native lands.

The reason why only Native areas within the contiguous United States are represented in the Cobell settlement is in part because Alaskan Native and Hawai’ian Natives operate under different relationships to the federal government, and were not impacted by the Dawes Act. The process of allotment was implemented and ended prior to indigenous and settler relationship between Alaskan Natives and Hawai’ian Natives were formalized, and land use was negotiated. No reservations or other Native lands in Alaska or Hawai’i were considered eligible under the Cobell Settlement.

View full-sized image

The map above shows all of the Native areas within the contiguous United States as defined by the 2010 United States Census. There are several areas that are designated Native areas which are not in fact reservations, but are lands that are held in trust by the federal government. This is particularly prevalent amongst the tribes that are now in Oklahoma. For example, Osage County, which is no longer considered a reservation by the federal or state governments is still represented as Native land.

One of the ways that the Department of the Interior has chosen to categorize the tribes eligible to participate in the Land Buy-Back program aspect of the Cobell Settlement is by determining which tribes have the highest rates of fractionation and prioritizing funds from the settlement to those tribes for land buy-back.

View full-sized image

The Department of the Interior designated forty tribes to be allocated $1.39 billion out of the $1.55 billion for fractionated land buy-back settlement funds, which leaves $163 million for the other 110 tribal lands with fractionated interests. These tribes in the "Top 40" are considered to be tribes most impacted by fractionation. Many of these tribes are concentrated in the middle of the contiguous United States, such as the Rosebud Sioux reservation and the Lake Traverse Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate reservation.

Since 2014 eighteen tribes have participated in the DOI's land buy-back program. The way that these program is implemented in a particular area is as follows. The DOI and the BIA hold many informational sessions in concert with tribal governments to inform people with IIM accounts about the process. The DOI determines the value of all fractionated land holdings in that land area, lands with valuable natural resources like minerals or oil will are considered more valuable than land that is used for agriculture or residences. Each IIM landholder is sent a monetary offer for their land which they can accept or refuse. If an IIM landholder accepts the offer made by the DOI their land will be purchased and put into trust for the tribe in question under the federal government.

View full-sized image

Unsurprisingly, many of the tribes that have participated most in the buy-back program are those tribes within the “Top 40” determined by the DOI. Though the ranges of accepted offers by people with IIMs is large, it is significant that acceptance rates begin at about 33%, or at least one third of offers made by the DOI by were accepted participating tribal members.

Reactions concerning the Cobell Settlement amongst Natives is not monolithic. People unsure about the benefits of tribes engaging in the settlement cite the initial mismanagement by the BIA and DOI as a good reason to decline any further offers concerning land from the federal government. Another concern is how much money is focused in on only forty tribes amongst hundreds that could possibly want to participate in a land buy-back program. This is complicated due to the legal process that confines the settlement in terms of historic legislation such as the Dawes Act, rather than general principles of land relations between the federal government and Native people. Additionally there is frustration with the valuation of the lands under review for buy-back, from the beginning of the Cobell suit there was great discrepancy in the amount of liability concerning mismanaged IIM accounts, ranging from $176 billion to numbers in the low millions of dollars.

Natives who are in favor of engaging with the settlement are often focused on bringing more land into the collectivity of a tribe, rather than held solely by individuals, especially the small plots caused by fractionation. The victory of the Cobell suit is certainly a historic moment in the legal relations between Native people in the United States and the federal government, as it is often considered the largest successful class-action lawsuit in the history of the United States. And the success of the suit can be understood as a loud recognition of the mistreatment and continued mismanagement of Native people’s land by the federal government.

The nature of the Cobell settlement and the subsequent land buy-back program implemented by the Department of the Interior and the Bureau of Indian Affairs is tied up in legacy of the settler colonial state that is the United States. The logic of a settler state is to limit, if not destroy the indigenous peoples and their practices, including their land use practices and sovereignty. The question that the question that Cobell settlement asks is whether engagement with the federal government of the United States on a legal basis is a worthwhile path towards Native sovereignty or if it simply reinforces the authority and power of the federal government over Native peoples and Native lands.