Indian Country

What is Indian Country?

Indian Country is legally defined as all land that has been set aside by the United States government for the use of Native Americans. These lands have a number of different legal statuses, and civil and criminal jurisdiction varies from one place to another. The most well known of the land holdings in Indian country are Indian reservations, although it also includes dependent Indian communities, and private allotments still held in trust(Pevar, 2012)

.The legal definition of a reservation includes all land that is within reservation boundaries. This might seem obvious, but this definition extends even to those plots of land owned by private individuals and therefore not held in trust by the federal government. Dependent Indian communities on the other hand are lands or physical spaces outside of reservations, but still under the administration of the federal government. They can include tribal housing projects, tribally owned buildings, and Native communities living on federal land.

The Pueblos are a primary example of dependent Indian communities. While the American Southwest was under Spanish and then Mexican control, the Pueblos were given citizenship and land grants recognizing that they owned their lands. When the U.S then gained control of the region through the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, they were forced to recognize any and all preexisting land grants and give citizenship to those Mexicans who remained on their lands, including the Pueblos. The result is that today the Pueblos own all their lands, although they have a protected status through the federal government. Indian Country also includes allotted lands which are either held in trust or held in restricted status. Trust allotments are assigned to individual Indians, but continue to be owned by the federal government. Restricted allotments on the other hand, are privately owned. Whether trust or restricted however, these allotments cannot be sold or leased without federal approval.

Certain Native communities and lands are excluded from Indian Country. Most are tribal lands which are privately owned and not under federal administration. But this also includes Alaskan Villages whose lands are exempt from state and local taxation like most Indian Country, but aren’t under the authority of tribal governments and aren’t held in trust. Hawaiian Homelands, although they are held in trust by the state of Hawaii, are not recognized as Indian Country by the federal government.

For more information on some of these definitions see the Census Bureau’s webpage on geographic terms and concepts. For a brief history and description of Indian Country and tribal nations, see the National Congress of American Indians report "An Introduction to Indian Nations in the United States." For information on allotment specific to each tribal nation, see the Indian Land Tenure Foundation’s page on that topic.

Where is Indian Country?

According to the National Congress of American Indians, tribal lands make up some 50 million acres in the United States, or about 5% of national lands. As of 2010, this included 334 reservations, the majority of which are all west of the Mississippi. Most of these reservations are less than 50 square miles, although approximately 7% of reservations are more than 1000 square miles(Frantz, 1999)

. In fact, most of the 50 million acres of Indian Country come from only a couple dozen reservations. The Navajo reservation, which is about the size of West Virginia, is by far the largest in the United States.While these figures only account for tribal reservations, Indian Country includes much more territory throughout the United States. Oklahoma for example, which has no reservations, is mostly Indian Country, full of allotments and dependent communities.

For more information on Indian Country locations see the National Congress of American Indians’ regional profiles. For statistical information on American Indians, tribal governments, and reservations see the Census Bureau’s Newsroom Archive.

Land Ownership

There are various ways by which land within Indian Country can be owned. The federal government, tribal governments, and individuals can all own land in Indian Country, although they have to be held under specific conditions or they would lose their status as Indian Country(Frantz, 1999)

. Most of Indian Country is lands, like reservations, which are held in trust by the federal government. Tribal trust lands can either be held and used in common by the entire tribe, or the tribal government can assign them to individual members. Similarly, trust allotments are plots of Indian Country which the federal government has assigned to individual Indians. The main difference with allotment however, is that tribal members become owners with restricted property rights, rather than just users, of those assigned lands.

In addition to trust lands, a significant portion of Indian Country is privately owned without any restrictions on their sale or lease. This includes land owned by tribal members as well as non-Indians. In these instances however, the lands remain Indian Country because they are either enclosed within a reservation or another piece of land purposefully set aside for Indians.

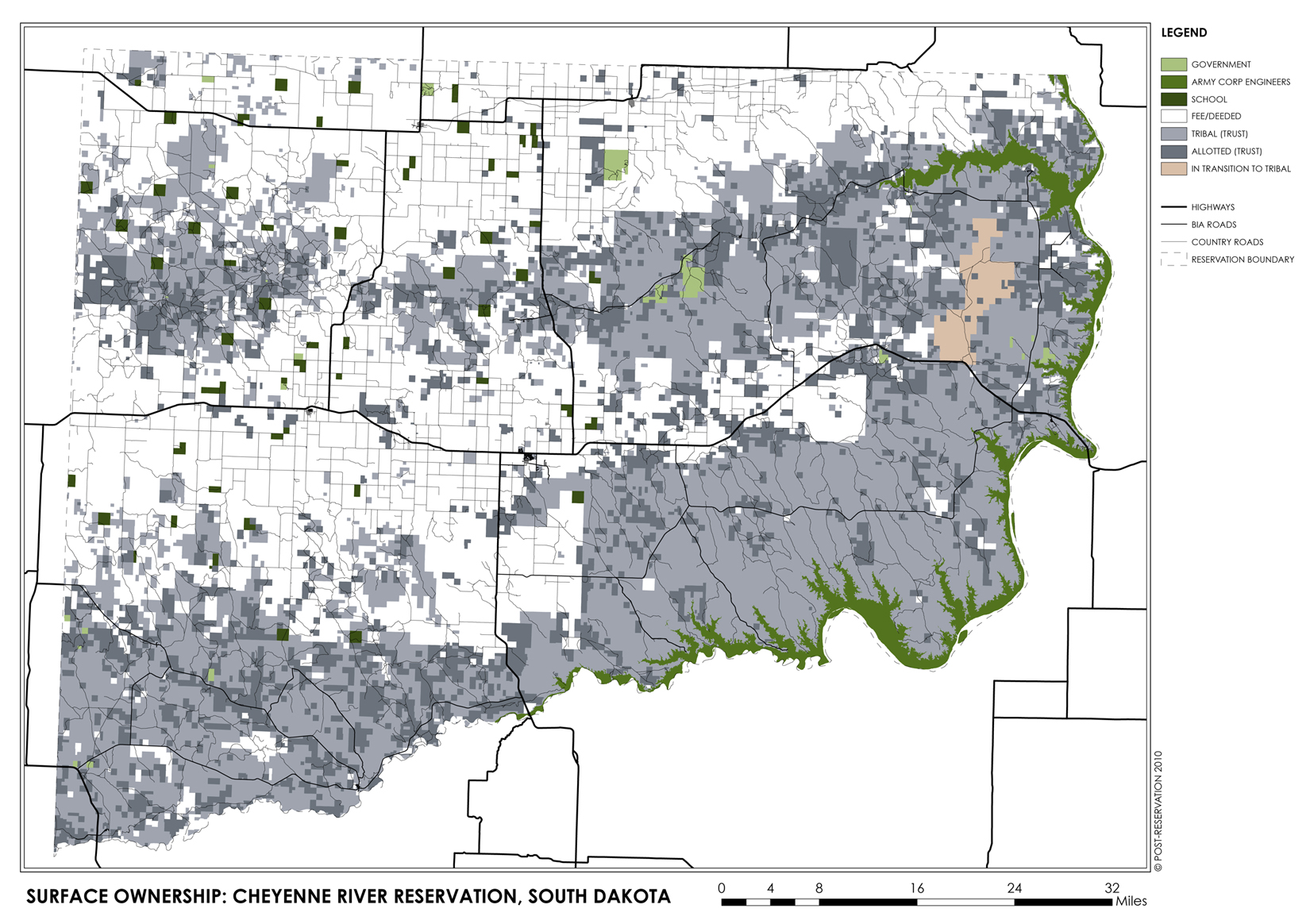

Checkerboarding: View full size image.

This mix of ownership within Indian Country, known as checkerboarding, has serious consequences for Native communities. For more information on checkerboarding, see the Indian Land Tenure Foundation’s webpage on that topic.

Fractionation

One of the most serious issues concerning tribal lands today is the fractionated heirship that comes from allotment. Under allotment legislation, if an allottee died without a will, their allotment stayed held in trust, but interests in the land were divided among all eligible heirs. Over the generations, this process of fractionation has made it so that the average allotment tract had 17 co-owners, although some are held by dozens or even hundreds of heirs. Of the 3.2 million owners of trust allotments, 86% own less than 2% of their ancestor’s original allotment(Shoemaker, 2003, 8)

.The fractionation of allotments is a problem, not only for the BIA which has to manage and account for all of these interests, but for tribes and allotment owners themselves. Allotment policy requires that the BIA obtain consent from a majority of co-owners before leasing or developing any land on an allotment. The difficulty of communicating with and reaching an agreement with so many different owners hinders tribal attempts to make efficient use of their lands, and stifles economic development. Worth noting as well, is that the costs of managing these fractionated interests can cost between 50% and 75% of the BIA’s entire land management budget

(Shoemaker, 2003, 8)

.For more information on fractionation see our page on that topic, Fractionation. For more information on how tribes and the BIA are trying to reform land management, see our page on land buy-back programs, Cobell Settlement.

Leasing

Trust land can be leased to Natives or non-Natives as long as the lease is in accordance with federal law and the original owner/beneficiary of the land consents. In cases of fractionation where consent of multiple beneficiaries may be hard to acquire, then the decision is left to the Secretary of the Interior to determine if it is best for the Natives. Because of the fractionated nature of tribal lands, the majority of agricultural lands are leased to non-Indians for cheap. The consequence is that the majority of profit from the land is funneled outside of the tribe. Types of trust leases include (1) farming and grazing leases; (2) mining leases; (3) oil and gas exploration leases; and (4) public, religious, educational, recreational, residential, or business leases. Each type has its own requirements and regulations to follow(Pevar, 2012, 64)

.For more information on tribal land leasing, see the Indian Land Tenure Foundation’s webpage on land management.

Jurisdiction

In terms of civil jurisdiction, tribes have the right to exercise civil jurisdiction over members of the tribe who reside on the reservation, and off the reservation when it comes to benefits, such as health care and voting rights. Generally, tribes have the right to exercise this civil jurisdiction over non-Natives who live on tribal land. However, tribes cannot exercise civil jurisdiction over non-Natives living off Native lands. This is the case unless an agreement has been made between the members of the tribe and the non-Natives, or if the tribe or reservations are being directly threatened. States do not have the right to exercise civil jurisdiction over members of a tribe, but do regulate non-Natives when it comes to sales tax. States can also regulate the sale of alcohol in Indian Country.When it comes to criminal jurisdiction on reservations, a tribe can exercise criminal jurisdiction only over its own members; they have no jurisdiction of non-Natives. However, the Major Crimes Act of 1885 classifies certain crimes that tribes have no matter of criminal jurisdiction in, including murder, manslaughter, kidnapping, rape, child abuse, and incest. In these cases, only the federal government may exercise criminal jurisdiction. The state may only interfere in cases of criminal acts between non-Native and non-Native. Additionally, P.L. 280 requires that California, Oregon, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Alaska, and Nebraska, as states, exercise criminal jurisdiction over the tribal lands within state boundaries

(Pevar, 2012, 128)

.